When body meets H1N1 flu

Two separate research teams have cataloged interactions between the H1N1 influenza virus and human cells, with one group reporting that human cells already contain powerful antiflu agents that also help defend against other viral infections, including West Nile virus and dengue.

Published online December 17 in Cell, both studies may help scientists build better flu-fighting therapies in the future.

One of the studies concentrated on learning how the body responds to the flu, says Stephen Elledge, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. Elledge and Abraham Brass led the study, which identified more than 120 human genes required by the H1N1 virus to infect a cell. For most of the genes, their removal stopped or slowed virus growth. But for three of the genes, removal actually helped the virus grow better, indicating that those genes are normally involved in fighting the virus.

These three genes encode proteins in a family called the interferon-inducible transmembrane family, or IFITM proteins. The proteins IFITM1, IFITM2 and IFITM3 are normally made at low levels in cells. Scientists knew that an immune-stimulating protein called interferon causes IFITM levels to rise, but haven’t known what increased levels of those proteins does for the cell.

Now, Brass, Elledge and their colleagues show that IFITM proteins help kill flu viruses, and that IFITM3 may be particularly important. That protein may help block flu viruses from entering host cells, though the team has not pinpointed the mechanism. IFITM3 also thwarts viruses such as dengue, West Nile and yellow fever, the team found.

“This [protein] blocks them all,” Elledge says. Increasing levels of IFITM3 might boost the body’s ability to combat the flu. And the team shows that blocking the protein in chicken and dog cells used to grow vaccine strains could make the virus grow better, possibly speeding vaccine development, he says.

If people have varying levels of IFITM3 in their cells, people with low levels may be more susceptible to flu, speculates Andrew Mehle, a virologist at the University of California, Berkeley. He also wonders whether a species’ versions of the IFITM proteins may determine which viruses can infect that species.

The other Cell paper documents the hundreds of interactions between the H1N1 virus and host proteins that take place during an infection. Previously scientists have studied how individual virus proteins interact with human cells. The new, large-scale screen reveals that the H1N1 flu virus’ 10 proteins connect to 1,754 human proteins in some way, report researchers led by Aviv Regev and Nir Hacohen of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard in Cambridge, Mass. Of those relationships, 87 are direct between flu and human proteins. Indirect connections make up the remainder and include some interactions that affect levels of human proteins in a cell.

On average, one influenza protein interacts with about twice as many human proteins as does one typical human protein with other human proteins, says Regev. The flu virus “really is sending many tentacles into the cell,” giving the virus a big impact on a host cell’s behavior, she says.

Both studies raise intriguing questions, Mehle says. “They both seem to lay the foundation for several careers right now,” he says. “It will be pretty exciting for the field to chase down these leads over the next two or three years.”

ibaL view: It will be interesting to discover Vitamin D's role in this.

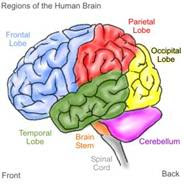

The Brain

The human brain is the most complex and least understood part of the human anatomy. There may be a lot we don’t know, but here are a few interesting facts that we’ve got covered.

1. Nerve impulses to and from the brain travel as fast as over 200 miles per hour. Ever wonder how you can react so fast to things around you or why that stubbed toe hurts right away? It’s due to the super-speedy movement of nerve impulses from your brain to the rest of your body and vice versa, bringing reactions at the speed of a high powered luxury sports car.

2. The brain operates on the same amount of power as 10-watt light bulb. The cartoon image of a light bulb over your head when a great thought occurs isn’t too far off the mark. Your brain generates as much energy as a small light bulb even when you’re sleeping.

3. The human brain cell can hold 5 times as much information as the Encyclopedia Britannica. Or any other encyclopedia for that matter. Scientists have yet to settle on a definitive amount, but the storage capacity of the brain in electronic terms is thought to be between 3 or even 1,000 terabytes. The National Archives of Britain, containing over 900 years of history, only takes up 70 terabytes, making your brain’s memory power pretty darn impressive.

4. Your brain uses 20% of the oxygen that enters your bloodstream. The brain only makes up about 2% of our body mass, yet consumes more oxygen than any other organ in the body, making it extremely susceptible to damage related to oxygen deprivation. So breathe deep to keep your brain happy and swimming in oxygenated cells.

5. The brain is much more active at night than during the day. Logically, you would think that all the moving around, complicated calculations and tasks and general interaction we do on a daily basis during our working hours would take a lot more brain power than, say, lying in bed. Turns out, the opposite is true. When you turn off your brain turns on. Scientists don’t yet know why this is but you can thank the hard work of your brain while you sleep for all those pleasant dreams.

6. Scientists say the higher your I.Q. the more you dream. While this may be true, don’t take it as a sign you’re mentally lacking if you can’t recall your dreams. Most of us don’t remember many of our dreams and the average length of most dreams is only 2-3 seconds–barely long enough to register.

7. Neurons continue to grow throughout human life. For years scientists and doctors thought that brain and neural tissue couldn’t grow or regenerate. While it doesn’t act in the same manner as tissues in many other parts of the body, neurons can and do grow throughout your life, adding a whole new dimension to the study of the brain and the illnesses that affect it.

8. Information travels at different speeds within different types of neurons. Not all neurons are the same. There are a few different types within the body and transmission along these different kinds can be as slow as 0.5 meters/sec or as fast as 120 meters/sec.

9. The brain itself cannot feel pain. While the brain might be the pain center when you cut your finger or burn yourself, the brain itself does not have pain receptors and cannot feel pain. That doesn’t mean your head can’t hurt. The brain is surrounded by loads of tissues, nerves and blood vessels that are plenty receptive to pain and can give you a pounding headache.

10. 80% of the brain is water. Your brain isn’t the firm, gray mass you’ve seen on TV. Living brain tissue is a squishy, pink and jelly-like organ thanks to the loads of blood and high water content of the tissue. So the next time you’re feeling dehydrated get a drink to keep your brain hydrated.